Self-portrait of Luca Scarabelli on roller skates

Photo © Luca Scarabelli

Portrait of Laura Paja on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Cesare Biratoni on roller skates

Photo © Luca Scarabelli

Portrait of Turi Rapisarda on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Sergio Breviario on roller skates

Photo © Luca Scarabelli

Portrait of Marco Torriani on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Cecilia Mendasti on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Marisa Casellini on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Memo Basso on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Carola on roller skates

Photo © Luca Scarabelli

Portrait of Max Tosio on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Diana Dorizzi on roller skates

Photo © Luca Scarabelli

Portrait of Al Fadhili on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Ermanno Cristini on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

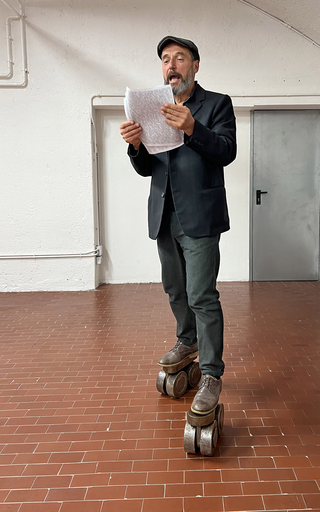

Portrait of Chris Terzi on roller skates during the installation of his exhibition Donne insolite at Riss(e) a Varese (30 octobre - 5 december 2021)

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Renata Boero on roller skates

Portrait of Valentina Scarabelli on roller skates

Photo © Luca Scarabelli

Portrait of Armando della Vittoria on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Carlo Buzzi on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Filippo Soli on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Angelo Leonardo on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Cecilia Mentasti on roller skates

Photo © Luca Scarabelli

Portrait of Andrea Pizzari on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

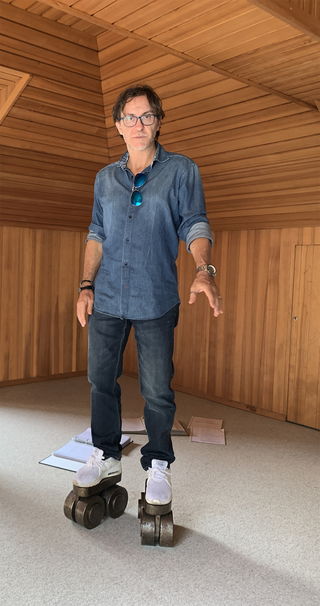

Portrait of Daniel Fuss on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Francesco Conti on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

Portrait of Valentina Bobbo on roller skates

Photo © Umberto Cavenago

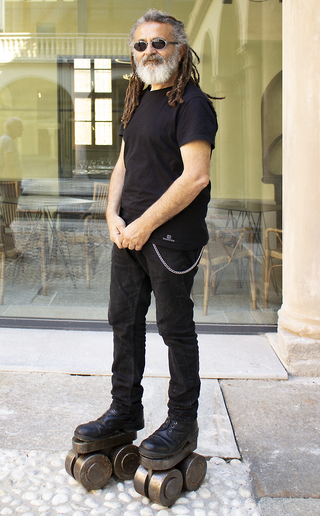

Portrait of Massimo Forchino on roller skates

Ritratto di Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo (marzo 2024)

Ritratto di Carlo Dell'Acqua

Ritratto di Mirco Marino sui pattini (marzo 2024)

Ritratto di Elisa Bollazzi - MICROCOLLECTION (marzo 2024)

© Armando della Vittoria

Social

Contatti

umberto@cavenago.info